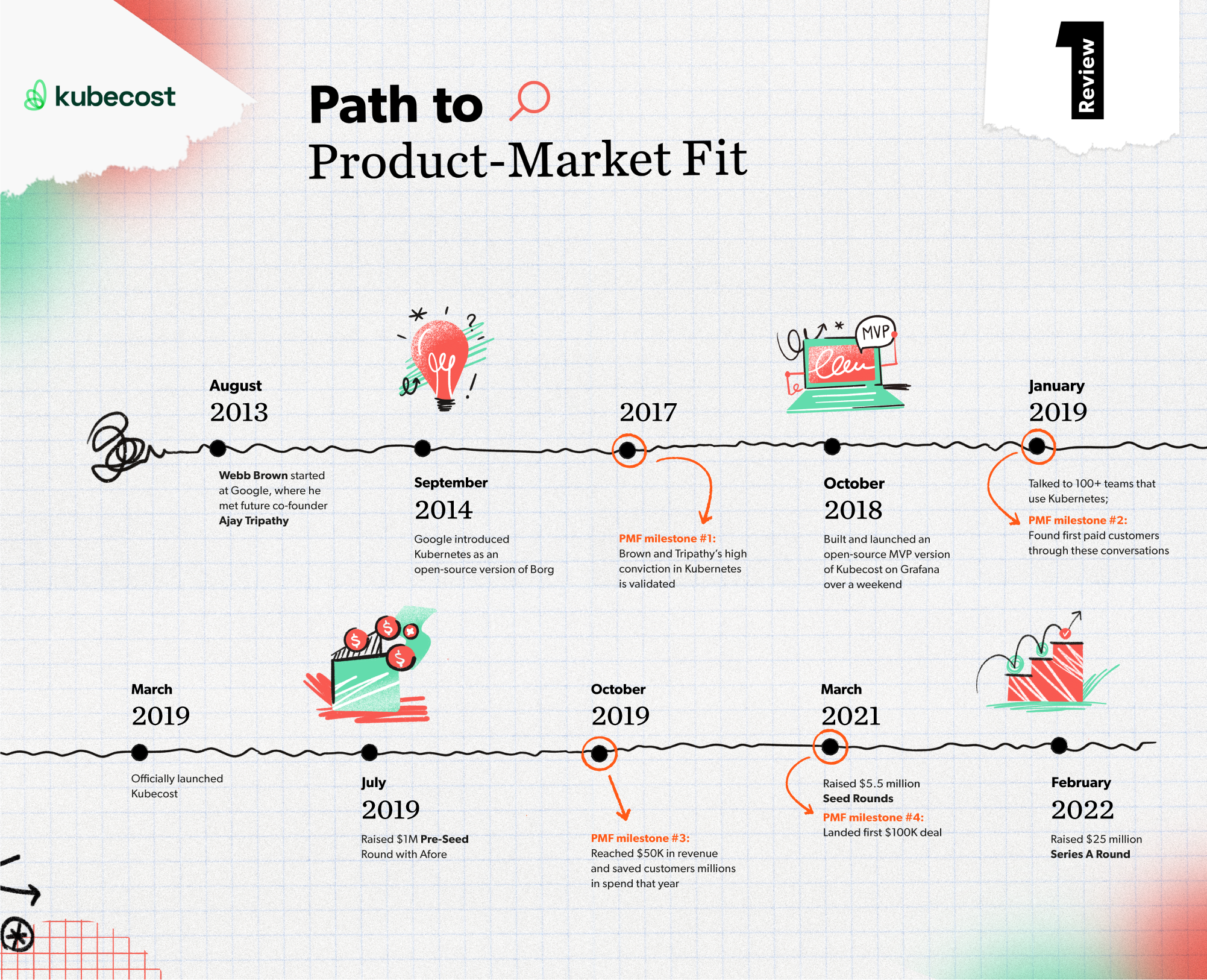

When Kubecost’s Webb Brown and Ajay Tripathy met at Google in 2013, they wouldn’t have guessed that they would start a company together six years down the road — but there were signs from the start.

“While we thought Google was awesome, we were always like, ‘what if we built this’ or ‘what if we did this’ or ‘someone needs to build X.’ It wasn't necessarily that we wanted to go start something together at that point — it was just that we discovered we both had a love for building things,” Brown says.

One of the most significant projects Brown and Tripathy worked on at the company was cost, health and performance monitoring for the Borg system, which solved for one of the biggest problems that every startup encounters once they pass a certain size: infrastructure management.

As a company grows, it has an increasing number of applications running across hundreds of servers that belong to different teams, departments, customers or environments. Manually orchestrating these systems, as you might imagine, is incredibly complex.

Google found a way to automate much of this process with Borg. And, recognizing the value of such a system, they released an open-source solution called Kubernetes in 2014 with the lessons they learned. Even from the earliest days, Brown and Tripathy had high conviction that it was going to be a widely adopted platform. But they also quickly noticed a problem that the earliest users were running into.

“The largest early users of Kubernetes were getting bills for millions a month from Google but couldn’t accurately tell where they were spending the money because of the complexities of the Kubernetes scheduler and the pricing structure of the cloud services the platform helps manage,” Brown says. “So engineers had no idea how to tune or optimize their infrastructure. As a result, there was a huge opportunity to improve efficiency.”

While Webb and Tripathy didn’t act on this insight at the time, the seed had been planted for their future startup idea.

EXPLORING IDEAS

After Brown left Google in 2017, he took some time off but continued to keep a close eye on Kubernetes. His hunch that it was going to be a widely-adopted platform was proving to be correct. Companies like Microsoft, RedHat and IBM were already using Kubernetes, and it was quickly becoming mainstream amongst startups.

He found ways to stay embedded in the Kubernetes ecosystem — attending conferences, maintaining relationships with people in the industry and staying tuned in to online conversations — and through these channels, continued to hear the same chorus of complaints from the teams that used Kubernetes. ”It was that question around pricing again, at all levels of the company. Engineering couldn't answer it, finance couldn't answer it, leadership couldn't answer it. I heard that same feedback in so many different forms.”

That’s when he started to think about potential solutions to the problem. There are a few reasons why price transparency is such a huge challenge. While Kubernetes itself is free, it manages a company’s cloud services, which tend to have opaque, complex pricing structures. This, combined with all of the automation that happens with Kubernetes, makes it difficult to understand the connection between a team’s decisions and the price they pay, and therefore makes cost management challenging.

What if Brown could address this problem by building an agnostic tool that tracks what all a company’s various apps are doing and ensure that nothing is being overutilized or underutilized? In 2018, Brown reached out to Tripathy — who had also left Google in 2017 and was consulting with Yelp at the time — to see if he would potentially be interested in pursuing this idea together. Tripathy was on board.

VALIDATING THE IDEA

With an idea on paper, Brown and Tripathy set out to validate two things: first, that the problem space was actually as large and urgent as they were assuming. And, second, that the solution they had in mind was the right one to solve their stated problem.

The validation phase is where many founders stumble. People tend to get overly invested in their initial idea, making it difficult to change course or iterate as they go. Brown and Tripathy wanted to find ways to avoid falling into this trap.

“It was really important for us to give ourselves the mental freedom to say, no, sorry, we've got this wrong,” Brown says.

We wanted to give ourselves the ability to be wrong and fail and learn something new and be comfortable with changing directions — as opposed to committing everything we have to make this particular path work.

Rather than investing a ton of resources upfront or being mentally married to their idea, they started with a less permanent and much more contained scope — or what they referred to as a project-oriented mindset.

A true MVP

To truly adhere to a project-oriented mindset, Brown and Tripathy decided to get an MVP out to users as fast as possible so that they had something tangible to react to. “We built an MVP literally over a weekend. It was built using another technology by the name of Grafana, which today is a really big observability platform. It had very little code written but was essentially a dashboard that could show you different Kubernetes cost trends and dimensions,” Brown says.

Along with the MVP, they published a Medium post to explain why they were launching this open-source project. In a matter of days, over 150 people had engaged with the product. This was enough of a positive signal for the co-founders to go out and start talking to potential users.

The benefit of this accelerated approach was that — since they didn’t spend weeks or months building, tinkering and fine-tuning their MVP — they could get their most important questions answered without being at risk of having the sunk cost fallacy influence their decisions.

“Most people thought we were crazy," Brown admits.

We were focused on answering questions like, what is the problem? Do people care? Are people willing to engage? We didn’t need 120 features to answer those. And sometimes that means being comfortable having a suboptimal solution for the sake of validating a hypothesis in the short term.

Strong customer pull

Brown and Tripathy wanted to deeply understand the pain points of their potential users — and make sure their solution was aligned. So they reached out to hundreds of teams that used Kubernetes, both at startups and larger companies, to hear what they had to say.

This is where many founders let their optimism bias creep in. It’s easy to misinterpret someone’s polite response as a signal of validation, which could lead you down the wrong path. To combat this, it’s critical to look for undeniably strong signals during your conversations.

For instance, when talking to potential customers, their eyes should light up. They should be engaged in the conversation and ready to pull out their wallets on the spot to pay for your solution. In short, there should be no space for doubt when it comes to validating your problem or solution through customer conversations.

Thankfully, that’s exactly the type of response Brown and Tripathy got when they unfurled their startup idea.

Teams weren't just saying that they were struggling with cost visibility — they were struggling in a way that they were willing to go try some totally unproven software. A bunch of them were willing to install our MVP and were already making feature requests. It just felt like we were being pulled in by these people, rather than us pushing our solution onto them.

In total, the co-founders spent two months interviewing about 120 teams. Along the way, they used these conversations to inform, tweak and fine-tune the shape of their solution. “At that point, we said, ‘OK, there's enough here to where we want to really start thinking seriously about what a real product would look like.’”

FINDING EARLY CUSTOMERS

Even before Brown and Tripathy officially launched, people wanted to pull the product out of their hands. “We actually found our first two to three paid customers from those initial conversations,” Brown says. “And we were like, ‘Wait, you actually want to pay us?’ We didn’t even have a company formed at that point.”

In March 2019, they officially launched Kubecost (which was called Stackwatch at the time) with a blog post and a production-ready solution.

At this point, most startups would have already started the process of raising their seed round. But instead, Brown and Tripathy chose to go the bootstrapping route. The reason, says Brown, is that he didn’t want to take that step until he felt extremely confident that they had a viable business idea.

I see a lot of founders who raise $5 million and immediately hire a team of 20. And I think this makes it so much harder to iterate quickly or spend meaningful time talking to users because you’re spending so much of your resources managing your employees and other parts of the business. I think it’s really important to give yourself the time and space to not skip that early validation stage.

To gauge the strength of their business, the Kubecost co-founders used willingness to pay as one of their key engagement metrics. “I think our very first customer paid us $99 a month. And then the next five were between $199 and $299. I remember when we got somebody to $1000 a month. That was when it started feeling like our solution was truly valuable.”

By 2020, Kubecost was generating more than $50K in revenue. Now confident that they had an idea worth pursuing, the team raised a $1 million pre-seed round. Since then, Kubecost has only continued to grow — signing their first $100K deal and raising a $5.5 million seed round in 2021 and, most recently, raising a $25 million Series A in 2022.

The team has also continued to stay tuned into their users, introducing significant product developments that add value for their existing customers — such as building automation on top of their foundational monitoring — as well as expanding their solutions to meet the needs of larger enterprise companies.

LOOKING FORWARD

Founders like Brown, whose startups are early but clearly on the path to product-market fit, offer us the benefit of having their learnings fresh in mind. Reflecting on the past four years, Brown offers this piece of advice to other entrepreneurs who are just getting started on their company-building journeys.

Too many founders, he says, get caught up in getting things ‘perfect’ before taking action. Having that bias towards action and getting things in front of users sooner rather than later, the way that he and Tripathy did with Kubecost, can help you iterate more effectively and — as a result — get to product-market fit faster.

“Being highly situational is so important. This means having a clear idea of what you’re trying to prove, at that moment in time, to either de-risk the business or move the ball forward in a material way.”