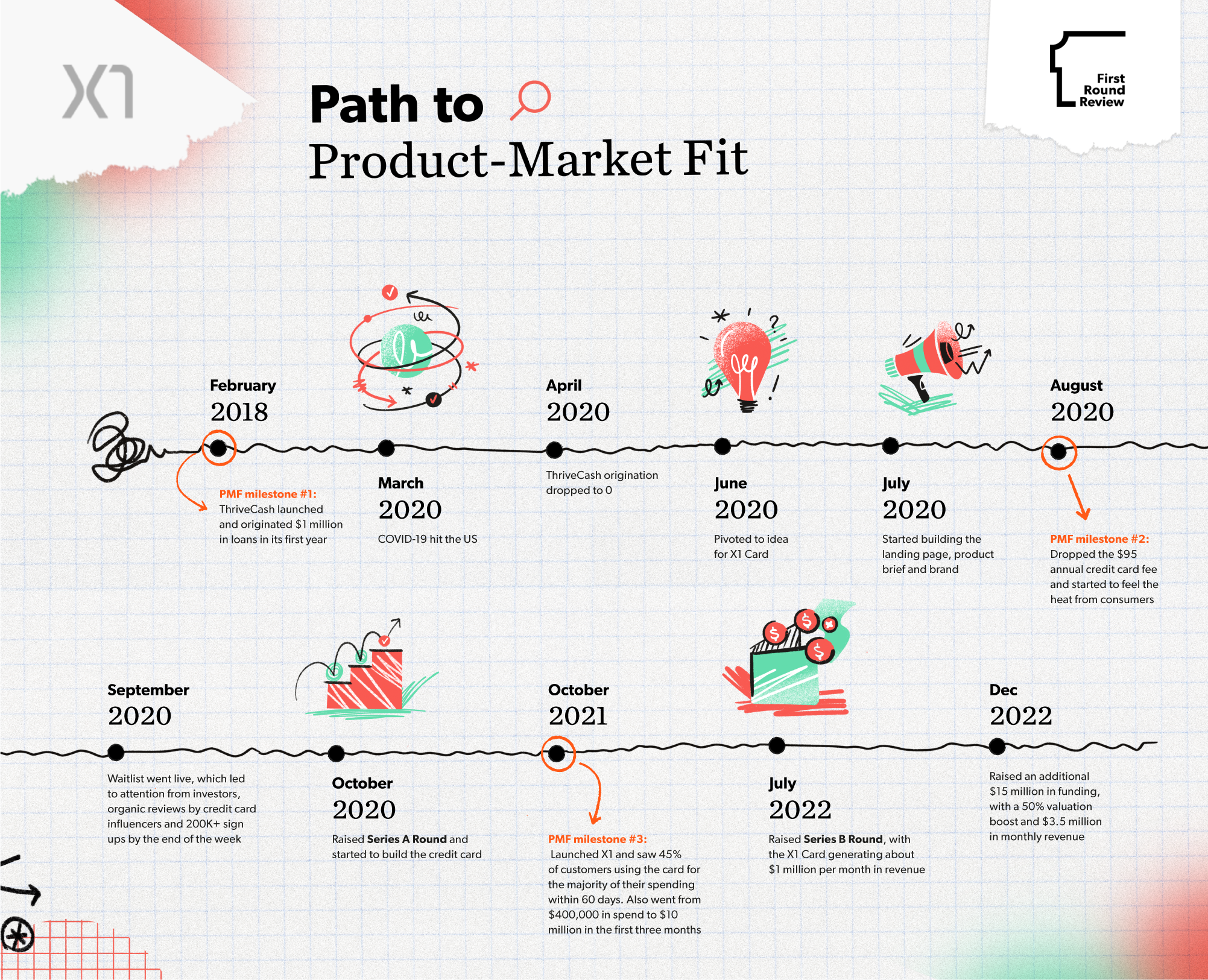

This is the fourth installment in our series on product-market fit, spearheaded by First Round partner Todd Jackson (former VP of Product at Dropbox, Product Director at Twitter, co-founder of Cover, and PM at Google and Facebook). Jackson shares more about what inspired the series in his opening note here. And be sure to catch up on the first three installments of our Paths to Product-Market series with Airtable co-founder Andrew Ofstad, Maven founder Kate Ryder, and Retool founder David Hsu.

When Deepak Rao launched ThriveCash in 2018, things looked promising.

A lending service for college students, the company launched on the campuses of New York University and Columbia University and originated $1 million in loans in its first year. Soon after, ThriveCash raised its Series A, expanded to other states and was on track to reach $30 million for the 2019-2020 school year.

Then COVID-19 hit.

By April 2020, origination had dropped to zero. Since most students turned to ThriveCash when they needed to travel or relocate for an internship, the pandemic rendered its services irrelevant.

“Students could now start an internship or a full-time job from their dorm or at their parents’ house,” says Rao. “They started getting laptops in the mail and could work from anywhere. So there was no need to move to a new place.” In short, the product-market fit they had worked so hard to achieve with ThriveCash evaporated overnight because of the sudden change in the market.

With only $3 million left in the bank, which gave the team six months of runway at their current burn rate, they waited several weeks to see if the situation would improve. It didn’t. So Rao gave his 15 employees the choice to opt into a salary cut in exchange for more equity (which they all took) and reduced burn by half to $250K per month, extending runway to about a year. Better, but still not enough. Rao knew they needed to pivot — fast.

EXPLORING IDEAS

To think of a new idea, Rao reflected on the shortcomings of ThriveCash’s model. According to him, his company had two fatal flaws: “One was seasonality. We had huge demand in the spring quarter but less so in the fall and winter. The second was that ThriveCash wasn't a daily engagement product. You could only get a loan once or twice a year.”

But Rao noticed something during the pandemic. “Even during COVID, people were still using their debit and credit cards every single day. Instead of spending money on travel and housing, they were spending money on electronics and Pelotons.”

In other words, a credit card didn’t present any of the same challenges that a loan did. And it was still in the financial services space, where Rao and his team already had a lot of experience. They decided to investigate further.

Digging into the data

ThriveCash had underwritten thousands of college students for personal loans and, as a result, had access to their credit reports. When parsing through this data, Rao noticed that almost 100% of students applied for a credit card within six months of graduating.

But what was surprising is that many of them were getting rejected by issuers like American Express and Chase. With no other options, these new graduates were often forced to sign up for lower-tier cards with spending limits around $1,000.

This puzzled Rao. The people applying for these credit cards had graduated with offers from companies like Google and Goldman Sachs, often making six-figure salaries right out the gate. Why weren’t they being approved for the best cards?

What he eventually realized is that credit card issuers have a very rudimentary underwriting process. “They typically ask for the user’s income and then look at their credit history to see if they own a house, which most 20-somethings don’t,” Rao says. “They just don’t have access to the data to be able to accurately underwrite these profiles.”

This, Rao discovered, was problematic for young professionals. He emailed surveys to former students he had email addresses for and found that low spending limits were one of their top three complaints when it came to credit cards — with the other two being transparency and rewards. “We had some people telling us that they couldn’t even buy a MacBook with their credit card,” says Rao.

That’s when he realized there was a huge opportunity to create a better consumer credit card — and Rao’s team was uniquely positioned to do it. Since they had to underwrite every student who took out a loan with ThriveCash, they had a deeper understanding of the process than most.

Embracing the pivot

At first, Rao wanted to create a card specifically for young professionals. “For the first three to four months after we had the idea, we were not willing to let go of our focus on college students. But I'm glad we did. I think that was the best decision in hindsight — to just let go and take advantage of this huge market. It took a very long time to get to that point.”

When you do a pivot, the hardest aspect mentally is deciding what to hold onto versus what to let go.

After taking some pages out of the playbooks of other founders like Stewart Butterfield and Elad Gil, he ultimately decided to think bigger. “I realized that we have this amazing insight. We know how to underwrite people better. We know that we can build a more modern experience. Why limit our market to only new graduates or young professionals? Why not just build the best credit card out there?”

ASSESSING THE MARKET

By June 2020, the team was all in on the credit card. To better understand the nuances of being a credit card issuer, Rao dug into companies like Chime and Cash App — all of which were deep in the financial service industry and, he assumed, were in the process of building their own credit cards.

He was shocked when he found out that not a single one of these companies offered a consumer credit card or even had an interest in creating one. Rao was even more surprised when he found out it would take a minimum of 12 months, but most likely 24 months, to launch a credit card. The reasons:

- Complex regulations. “When you spend money on a debit card, it's your own money. But with a credit card, every single purchase is technically a loan. So the regulations around it are very intense and figuring out how to build a product around those regulations is challenging,” Rao says.

- Capital constraints. Launching a credit card requires a massive injection of capital upfront — something you typically get from an issuing bank. But all the banks Rao met didn’t feel comfortable partnering with them due to their lack of funds. “Keep in mind that our bank balance was going down rapidly at this point. We only had like $2 million dollars left.”

- Limited options for a processor. By far the biggest obstacle was a lack of access to a processor, which is what the credit card is built on. According to Rao, modern card issuing providers like Stripe and Marqeta don't support consumer credit cards, and there are only a handful of legacy processors that do. Many of these companies were founded in the ‘80s and hadn't evolved their infrastructure to meet the requirements of a modern consumer, making them extremely challenging to work with.

With less than $2 million in the bank, no product and not enough progress to make a new fundraise possible, Rao was in a tight spot. So he made an unconventional call. “We decided to use our remaining money to get validation and just launch a waitlist — without the card.”

BUILDING TOWARDS LAUNCH

The waitlist was set to launch on September 17, 2020. Even though the card wouldn’t be released on the same day, there was still a lot Rao and the team had to build ahead of time:

Choosing the name

Rao spent a lot of time choosing a name for the card. He knew it had to be something memorable. Something that would stick in people’s minds and eventually allow them to expand into a series of credit cards that target different consumer segments — similar to how American Express has its Gold, Platinum and Centurion offerings. Rao also wanted a name that was a blank canvas — one that didn’t have any prior meaning attached to it and could give them the freedom to brand their card however they liked.

While brainstorming, Rao drew inspiration from a passage in the memoir, "Shoe Dog," by Nike co-founder, Phil Knight:

"...seemingly all iconic brands — Clorox, Kleenex, Xerox — have short names. Two syllables or less. And they always have a strong sound in the name, a letter like 'K' or 'X,' that sticks in the mind.”

This resonated with Rao, so he decided to call the company X. But when he went to purchase the domain X.com, he discovered that it was already taken — by none other than Elon Musk.

“I actually got an investor to email Musk to see if he would sell us the domain. No response, of course,” says Rao. “But then, taking inspiration from premier sports leagues like Formula 1 Racing and Ligue 1, we just decided to combine X with the number 1. Luckily, X1.co was available for a few thousand dollars and, as it turns out, X-1 was the name of the first plane to break the sound barrier, so it ended up having a really cool connotation.”

Perfecting the landing page

Since they didn’t have the physical product yet, Rao knew the landing page had to be extremely strong to find the validation he was looking for. He labored over every single detail — from each line of copy to the way the card was depicted on the website.

For example, one of the ways that they brought the X1 Card to life was by adding a “hear the metal” feature that still lives on the website today.

“I read somewhere that the Beats headphones had extra weights in them to make them feel premium,” says Rao. “We wanted to do something similar with X1 Card and emphasize the weight of the card, which was going to be made of 17 grams of stainless steel. So we actually recorded the sound of the card dropping on a metal desk and added it to the landing page.”

Even though the card didn’t exist yet, Rao wrote what he describes as “the best product brief of his life” so that people would understand the features of the X1 Card. This was reflected on the website and included:

- A sleek, easy-to-use app.

- Up to 5x higher spending limits compared to the standard credit card.

- 2X to 4X point on every purchase, redeemable at merchants like Peloton, Patagonia, Allbirds and Airbnb.

- The ability to create disposable “virtual” cards and cancel subscriptions with one click.

Finalizing the details

Leading up to the announcement, Rao wanted to gut-check whether the idea for his credit card would land. So he conducted countless phone calls with college students he had originally found through ThriveCash. He walked them through the landing page and described the benefits of the card — from the higher spending limits to the generous rewards terms.

The response, to Rao’s disappointment, was lukewarm. In other words, the product-market fit wasn’t there. Rao knew that people should want to pull the product out of his hands at this point.

Consumer products have to be jaw-dropping. Otherwise, they’ll never work out. Whether people love it or hate it, you want to make sure they’ll 100% have something to say about it.

“Everyone felt like it was cool, but it wasn't astounding,” he says. Through his conversations, he learned that the problem was because of the $95 annual fee. “Once you have to pay $95 for something, you ask yourself if it’s really worth it. So we were like, ‘OK, what would make this a no-brainer for people?’”

Five days before the waitlist was set to go live, the team decided to get rid of the annual fee. They updated the landing page copy, changed the press release and hoped that this change was enough to entice people into signing up.

FINDING TRACTION: THE “AHA” MOMENT

After removing the annual fee, something changed.

Rao’s younger brother started sending screenshots of texts he was receiving from friends — all eager to sign up for X1. Even before the launch, word got out about the card and conversations started to organically pop up on Reddit. They were finally starting to find the heat from consumers.

“After I removed the annual and talked to a few people, they were like ‘Whoa, you're gonna give me all this stuff for no annual fee?’ The tone started changing, and that's when I knew we had something.”

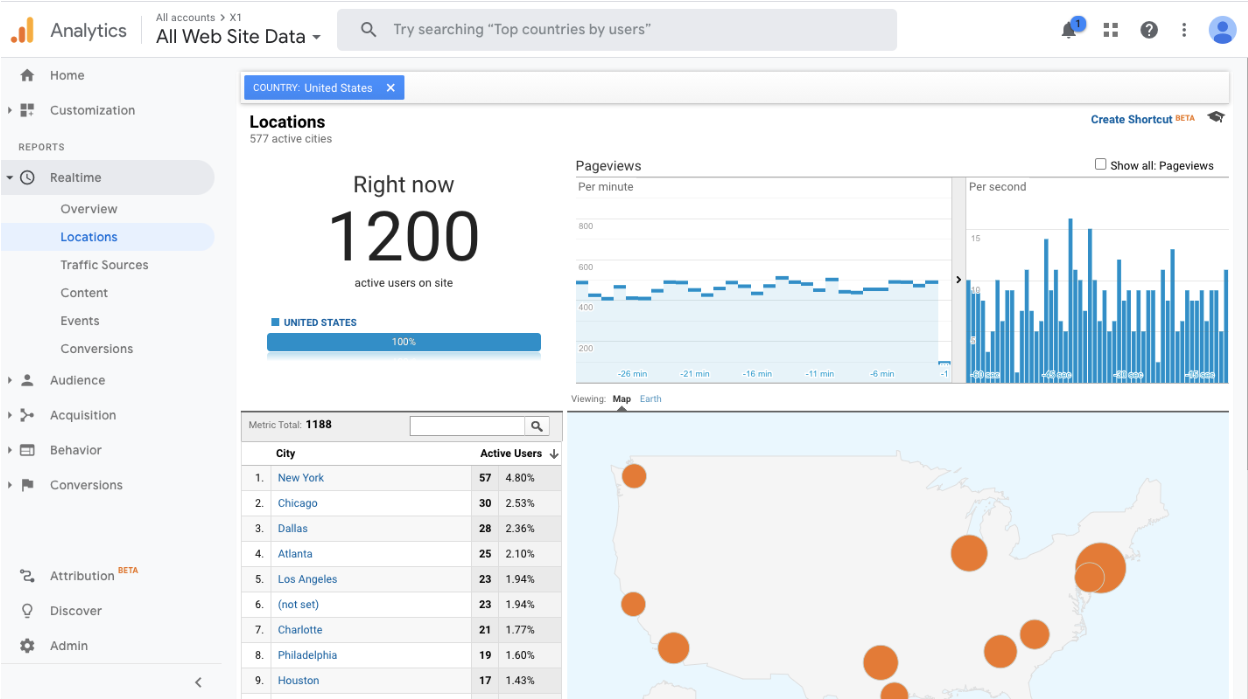

After much anticipation, the waitlist launched on September 17 at 6 a.m. PT, along with a TechCrunch exclusive. By 10 a.m. PT, the site had crashed. “We could not handle the queue of the waitlist,” says Rao. “We were getting around 1,000 signups per minute.”

The X1 Card went viral across social communities as well. Consumers and investors alike tweeted about the announcement. “Marc Andreessen followed me and liked the announcement tweet. And then Chamath Palihapitiya tweeted to ask if he could get a card. It was surreal,” says Rao.

X1 even started trending on YouTube after credit card influencers created organic reviews about the product. By the end of the first week, they had over 200,000 signups.

THE PATH FORWARD

After one year of building, finding the right processor and bank partner and raising a round of funding, the X1 Card launched to the waitlist in October 2021.

Judging from the positive responses and exclusive article in WIRED, the wait was well worth it — and it’s clear that a huge part of this was due to the exceptional attention to detail. Everything, from the design of the card to the product packaging, was thoughtfully designed to maximize the consumer experience and to encourage word-of-mouth growth.

“We used the manufacturer that built the AmEx Platinum to design our card,” says Rao. “We designed it so that there’s no personal information on the front of the card so that people can take pictures of it. I wanted to make the product very photogenic so that it’s visible on social media platforms.”

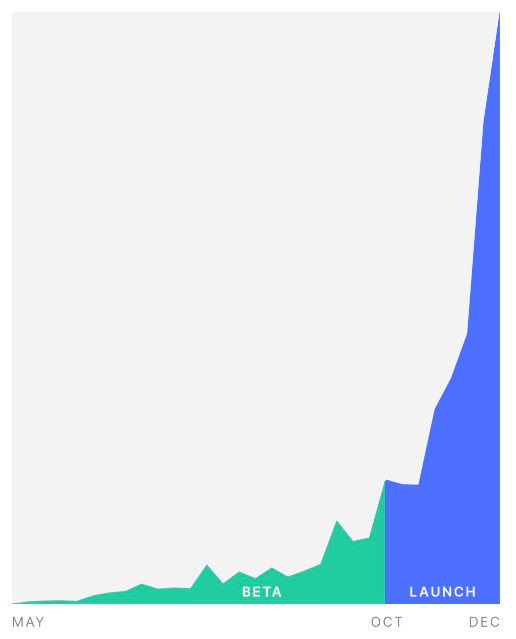

In the first three months of launching, X1 saw an explosion in growth (as seen by the chart David Sacks tweeted below) and went from $400,000 in spend to $10 million.

Today, the company processes $60 million in monthly spend and generates $3.5 million in revenue each month; X1 has customers in all 50 states and has 45 employees; and Rao raised an additional $40 million in funding in 2022.

Rao’s path to finding product-market fit was long, winding and looked very different from the standard Silicon Valley success story. But that, if anything, is one of the most valuable lessons that he wants to impart to other founders.

“Miles Davis once said, ‘it took me years to learn how to play like myself.’ That quote stuck with me. It reminded me that there's no common archetype of a person who can succeed. As a founder, it’s important to stay true to yourself and not chase the Mark Zuckerberg or Jack Dorsey success story because there are different ways to find success. I had to go through a very hard time in order to realize that.”